$50=,9:0;@6-#,55,::,,56?=033,$50=,9:0;@6-#,55,::,,56?=033,

#!#,55,::,,!,:,(9*/(5+9,(;0=,#!#,55,::,,!,:,(9*/(5+9,(;0=,

?*/(5.,?*/(5.,

6*;69(30::,9;(;065: 9(+<(;,"*/663

B"64,;04,:.0=05.<70:;/,:;965.;/05.C6>>64,5*/(9;,9B"64,;04,:.0=05.<70:;/,:;965.;/05.C6>>64,5*/(9;,9

:*/663;,(*/,9:9,4(059,:030,5;05(5,+<*(;065(34(92,;73(*,:*/663;,(*/,9:9,4(059,:030,5;05(5,+<*(;065(34(92,;73(*,

9,;*/,5662

$50=,9:0;@6-#,55,::,,56?=033,

.*662=63:<;2,+<

6336>;/0:(5+(++0;065(3>692:(;/;;7:;9(*,;,55,::,,,+<<;2'.9(++0::

(9;6-;/,"6*0(3(5+ /036:67/0*(36<5+(;065:6-+<*(;06564465:

!,*644,5+,+0;(;065!,*644,5+,+0;(;065

6629,;*/,5B"64,;04,:.0=05.<70:;/,:;965.;/05.C6>>64,5*/(9;,9:*/663;,(*/,9:

9,4(059,:030,5;05(5,+<*(;065(34(92,;73(*, /+0::$50=,9:0;@6-#,55,::,,

/;;7:;9(*,;,55,::,,,+<<;2'.9(++0::

#/0:0::,9;(;0650:)96<./;;6@6<-69-9,,(5+67,5(**,::)@;/,9(+<(;,"*/663(;#!#,55,::,,

!,:,(9*/(5+9,(;0=,?*/(5.,;/(:),,5(**,7;,+-6905*3<:065056*;69(30::,9;(;065:)@(5(<;/690A,+

(+4050:;9(;696-#!#,55,::,,!,:,(9*/(5+9,(;0=,?*/(5.,69469,05-694(;06573,(:,*65;(*;

;9(*,<;2,+<

#6;/,9(+<(;,6<5*03

(4:<)40;;05./,9,>0;/(+0::,9;(;065>90;;,5)@9,;*/,5662,5;0;3,+B"64,;04,:.0=05.

<70:;/,:;965.;/05.C6>>64,5*/(9;,9:*/663;,(*/,9:9,4(059,:030,5;05(5,+<*(;065(3

4(92,;73(*,/(=,,?(405,+;/,D5(3,3,*;9650**67@6-;/0:+0::,9;(;065-69-694(5+*65;,5;

(5+9,*644,5+;/(;0;),(**,7;,+057(9;0(3-<3D334,5;6-;/,9,8<09,4,5;:-69;/,+,.9,,6-

6*;696- /036:67/@>0;/(4(16905+<*(;065

:/3,,5+,9:65(169 96-,::69

&,/(=,9,(+;/0:+0::,9;(;065(5+9,*644,5+0;:(**,7;(5*,

:/3,,5+,9:65,0((05!(1(">(4@9(5*,:(97,9

**,7;,+-69;/,6<5*03

0?0,#/647:65

%0*, 96=6:;(5+,(56-;/,9(+<(;,"*/663

90.05(3:0.5(;<9,:(9,65D3,>0;/6E*0(3:;<+,5;9,*69+:

“Sometimes giving up is the strong thing:” How women charter school

teachers remain resilient in an educational marketplace

A Dissertation Presented for the

Doctor of Philosophy

Degree

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Gretchen N. Cook

May 2024

ii

Copyright © 2024 by Gretchen N. Cook

All rights reserved.

iii

DEDICATION

This dissertation is dedicated to all women teachers. Especially, those who entered the

field with hopes to make serious change. I see you, and know your struggles. I also dedicate this

to all the students who have been willing to be members of my classroom, challenge my

thinking, and push me to be a better teacher. I love you all and knowing that you are the soon to

be leaders of this world gives me hope!

Most importantly, this is dedicated to my two beloved dog sons—Dylan and Otis. While

these two are not physically on this earth to witness this accomplishment, they sat by my side for

three years as I worked towards this milestone. Otis, you reminded me to stay sane and that

caring for you was more important than any type of work. Dylan, you changed my life. You

taught me patience, empathy, and how to accept love. Dylan, you healed me from pain.

I also dedicate this to my cat children—Maisy and Sanders. These two little sneaks have

added paragraphs of nonsense to my dissertation as they run across my keyboard each time I

refill my coffee. I also dedicate this to my dog son Truman. Truman and I went through teething,

potty training, and his “teen” years as I worked on this behemoth. Truman you are a constant

reminder that I can do anything, and to be confident in myself.

I also dedicate this to the girl I once was. I was lost. Re-storied my life to survive. To

young Gretchen, thank you for bearing the burden so I could become the woman I am today.

While some folks might argue what is chronicled here is fiction, it is my non-fiction and my

reality. As a reader, it is your responsibility to interpret it and choose what meaning you shall

take from it.

“There is fiction in the space between

The lines on your page of memories

Write it down but it doesn’t mean

iv

You’re not just telling stories

There is fiction in the space between

You and reality

You will do and say anything

To make your everyday life seem less mundane.”

-Tracy Chapman

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe my devotion and love of academia to Dr. Nicholas and Ms. Baron. I experienced a

pivotal turning point in my educational journey in Dr. Nicholas’s eleventh-grade philosophy and

Ms. Baron’s advanced placement English classes. Prior to this point, I was a good writer and

student but did not particularly enjoy or value school. The teachers of these classes made

learning real-world applicable, differentiated assignments, infused me with a thirst for

knowledge, and made visible to me how the knowledge I was gaining would benefit my life. To

this day, I remember everything I learned in those classes and try to model my own professional

practices on those teachers. These teachers gave me an incredible gift—a passion for learning—

and in my naïve teens I could not fully comprehend this privilege. This “gift” inspired a desire

to pass this on to others.

I would be remiss in not thanking my powerful and compassionate committee members.

Thank you to Dr. Anderson for giving me the first opportunity to produce and publish scholarly

writing. You literally held me by the hand throughout the publication process. Thank you to Dr.

Harper for advancing my academic writing, and continuously pushing me to improve through

feedback. Thank you to Dr. Swamy for introducing me to Wacquant and changing my life with

Bourdieu and Practice Theory. Most of all, Dr. Cain I would not have the experience, writing

ability, and interview experience that I exit UTK with, had it not been for you taking me under

your wing and providing a very inexperienced student with a wealth of opportunities. Also, thank

you for always being willing to chat about Mothman. I also wish to thanks Dr. Barbara Thayer-

Bacon, who without, I would not have found my place here at UTK, and I thank her for always

being there to put my obsessive thoughts at ease.

vi

To the dedicated friends and former students who helped me bring the ethnodrama to life,

thank you. I am forever grateful to life you brought to this research and the Saturday you

sacrificed for me. Thank you to Caleb Cho, Cross Fuller, Jessica Summers, and Amelia Zahn.

To my parents, thank you for making school a priority. I did not appreciate it at the time

but this is where I have found my place.

To my wonderful husband, Chris, thank you for calming me down when I was stressed

out about due dates five months down the road. Thank you for moving across the state to support

my dream, and carrying our financial burden. Most of all, thank you for sending me funny

ChatGPT stories when I needed them the most, and being the best partner and animal dad I could

have ever dreamed of for 29 years.

vii

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this three manuscript dissertation is to explore the habits and enduring

patterns created by neoliberal structures that dictate how women teachers should behave within

the culture of a charter school and uncover how participants resist and describe their own

resiliency within the charter school institution. Specifically, this work is grounded in the

assumption that teacher success in the labor force is inhibited by institutional rules that are

ultimately harmful, and cause teachers to leave the field of teaching (Boe et al., 1997; Olsen &

Anderson, 2007; Peske et al., 2001; Standeven, 2022; Wenk & Rosenfled, 1992). To critique the

culture of charter schools, and to interrogate systemic inequities I will explain how Practice

Theory can add insight to the education process, and how agents have the possibility to change

their habitus and resist (Bourdieu, 1977). The research questions that will guide this dissertation

include the following: How can documentary narrative analysis be used to allow a researcher,

with insider knowledge, to give voice to the stories of participants, in order to examine the

neoliberal structures, inherent in charter schools, that create a habitus?; How did I use agentive

action, as a woman teacher, to remake the social structure of the charter school institution?; Do

women teachers resist the hidden rules of the charter school institution? If so, how?; and How do

women who work as charter school teachers describe the techniques they have developed to in

order to remain working as teachers?

This application will add nuance to the current research landscape, but on a broader level

it introduces a new approach to considering educational policies through the bodies and fields of

women teachers. This approach has the potential to provide insights into how women charter

school teachers might maintain resilience in the field, and highlight the ways in which teachers

who have become disillusioned with the field can make sense of their role within the charter

viii

school field which could lead to retention in the field, and recreation and disruption of ways of

policy embodiment.

Keywords: autoethnography, Practice Theory, charter school, ethnodrama, narrative

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I .................................................................................................................................. 1

Theoretical Framework .......................................................................................................... 17

Research Questions ................................................................................................................. 26

Manuscript Overviews............................................................................................................ 29

Manuscript 1........................................................................................................................ 30

Manuscript 2........................................................................................................................ 36

Manuscript 3........................................................................................................................ 40

Positionality ............................................................................................................................. 47

References .................................................................................................................................... 53

CHAPTER II ............................................................................................................................... 73

Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 74

Review of Literature ............................................................................................................... 77

Theoretical Framework .......................................................................................................... 83

The Study: The Educational Labor of Women Charter School Teachers ........................ 90

Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 91

Findings .................................................................................................................................... 97

Discussion................................................................................................................................. 99

References .................................................................................................................................. 102

CHAPTER III ........................................................................................................................... 112

Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 113

Review of Literature ............................................................................................................. 115

Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................................ 121

Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 127

Findings .................................................................................................................................. 131

Discussion............................................................................................................................... 143

References .................................................................................................................................. 151

CHAPTER IV............................................................................................................................ 159

Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 160

Review of Literature ............................................................................................................. 161

Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................................ 165

x

Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 168

Findings .................................................................................................................................. 178

Discussion............................................................................................................................... 186

References .................................................................................................................................. 193

CHAPTER V ............................................................................................................................. 203

References .................................................................................................................................. 211

APPENDICES ........................................................................................................................... 213

Appendix A ............................................................................................................................ 213

Appendix B ............................................................................................................................ 215

Appendix C ............................................................................................................................ 225

VITA........................................................................................................................................... 226

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

2

Ever since the landmark introduction of the 1983 report “A Nation at Risk

1

,” politicians

and the public have viewed the United States education system as failing. To remedy this, U.S.

education has been targeted by neoliberal education reform efforts (Hunt & Staton, 1996).

Neoliberal or neoliberalism is a political approach that favors free-market capitalism,

privatization, deregulation, and reduction in government spending (Spring, 2015). The education

sector is introduced to neoliberalism through applying an economic theory, or marketizing, to

curricular reform and schooling (Sturges, 2015). Schools are destabilized by such reforms

(Sturges, 2015) and hegemonized

2

, in that educators cannot separate their actions from

institutions and the neoliberal ontological commitments that dominate the education sector

(Apple, 2012). These efforts aim to privatize public education and create competition between

the private and public sector, while claiming to promote excellence, efficiency, and

accountability (Spring, 2015). Examples of destabilizing, privatizing reforms include school

choice, voucher programs, and charter schools (Hursh & Martina, 2016). Ultimately, critics

argue that neoliberalism fails to achieve its goals of efficiency and excellence because markets

never work as intended and are never neutral (Hursh & Martina, 2016).

The birth of charter schools represents a great neoliberal impact on the education field.

Charter schools did not emerge as a U.S. phenomenon until the mid-2000’s (Noguera & Syeed,

2020). To early charter advocates, educators could establish new schools that would disrupt and

1

This report from the United States Commission on Excellence in Education is considered a turning point in

education. It implied that the American education system was failing, and was the spark for local and national

education reforms (Spring, 2015).

2

Gramsci (1971) introduced the concept of hegemony. The foundation for Gramsci’s theory begins with the idea

that parties have been where leaders emerge, and parties serve as an arm of the “state.” Even so, every party is

representative of a social group and they function by balancing and executing their interests onto other groups. With

these parties working in service to the head of the state they help give consent to state action, but there is more

power in consent than in exertion on the part of the leader. However, cultural concerns are often disguised under

political concerns. In simple terms, hegemony is control exerted by the dominant group and won through ideological

consent.

3

promote innovation, and create competition in the education (Nathan, 1997). There were high

hopes for charter schools to be laboratories for innovation that would develop and share new

educational practices that would move the field of education forward at a rate correlating with

changes occurring in the business and industrial fields (Welsh, 2006). Supporters of charter

schools claim these institutions undermine the monopoly of public school districts and better

serve marginalized families and communities (Chubb & Moe, 1990), which falls under the basic

assumption of neoliberalism that privileges the private sector over the public.

Educators are also destabilized, and become disposed with the field by the institutional

trauma inflicted by neoliberal school reforms (Standeven, 2022). Legislators put measures, such

as school choice or No Child Left Behind, in place to control and surveil teachers. These

measures work against teachers because they serve to control and surveil them. Teachers are

negatively impacted by such surveillance, and this may cause some teachers to leave the

profession (Standeven 2022; Sloan 2007). Teachers are de-skilled through accountability

measures, and are viewed as mere technicians. Of course not all accountability measures are

harmful, teacher practice and student performance is quantified through these efforts (Spring,

2015). However, some advocates acknowledge that these accountability measures ensure that

teachers are delivering a standard curriculum to all students, but this can have negative results in

added pressures for teachers, who fear they are losing control over their own curriculum and

personal autonomy (Hubbard & Kulkami, 2009; Sloan, 2007). Ultimately, teachers ask less of

their students to avoid student resistance and the act of following these measures leads to a

narrow proficiency-based curriculum (Sloan, 2007).

To set the foundation for my work I will chronicle the impact of neoliberalism on

education, provide contextualization for charter schools, illustrate the gendered experience of

4

teaching in the U.S., and address how Practice Theory (Bourdieu, 1977) can provide a tool to

analyze how charter schools alter educational work and embody structures of labor discipline. I

will complete a three manuscript dissertation, and what follows provides a basis for this work.

Across this research, I will explore the habits and enduring patterns created by school institutions

that dictate how teachers, particularly women teachers, should behave within the culture of a

charter school and uncover how women teachers describe their own resiliency within the charter

school institution. My aim is not to solve a problem but to critique the culture of charter schools,

interrogate systemic inequities, and utilize Practice theory to uncover how agents have the

possibility to change their habitus and resist (Bourdieu, 1977)—all in service to retain teachers in

the field.

The Impact of Neoliberalism

Tenets of neoliberalism or the neoliberal state include individual property rights, the rule

of law, and free markets and free trade in order guarantee individual freedoms (Harvey, 2005).

Researchers have noted that neoliberalism includes the naturalization of the temporary (Sturges,

2015), a weak state (Apple, 1993), and a constant cycle of attempting to save and revamp the

system (Aalbers, 2013). Additionally, the idea of neoliberalism is associated with fiscal austerity,

deregulation, and reduction in government spending.

It has been criticized for posing a threat to democracy, workers’ rights, self-

determination, and giving too much power to corporations (Stedman Jones, 2012). Neoliberalism

is not to be confused with liberalism, in the political sense. An invisible hand is extended upon

the free market by guiding all forms of social action through neoliberalism, under the premise

that it promotes efficiency, but it is guided by control over politics of the body, standards, values,

and conduct (Apple, 1993). Public infrastructures are viewed to breed dependency and

5

bureaucracy, and competition offers a solution to inspire creativity and efficiency (Wilson,

2018). In theory, the construct of neoliberalism supposes that through competition, individuals,

the government, and companies will desire innovation and create a better social world, where the

very best people and ideas emerge (Wilson, 2018).

Hursh and Martina (2016) further clarified neoliberalism by calling it a dominant world

view that favors market-based decisions and individual competition. However, they argued that

neoliberalism fails to achieve these goals because markets never work as intended and are never

neutral (Hursh & Martina, 2016). At a social and community level, neoliberalism acts in direct

opposition to the common good (Hursh & Martina, 2016). In other words, the good or welfare of

the community is replaced by the welfare of the individual. Consequently, society embraces the

idea that decision making based on markets is superior to making decisions based upon

individual community needs (Block & Somers, 2014). Similarly, Wilson (2018) viewed

neoliberalism as a set of social, cultural, and political and economic forces that places

competition at the center of the social world. The ideological project of neoliberalism masks its

actual intentions. In reality, education is not deregulated but re-regulated (Aalbers, 2012).

Neoliberalism in Education

Policy makers introduce neoliberalism to the education sector by economizing education,

which means school outcomes are now judged in economic terms (Spring, 2015). Broadly, the

introduction of corporate structures to education permits corporate influence over school

policies, quantitative measures to judge school effectiveness, curriculum based on workplace

skills, and shaping behaviors in schools to meet the needs of a free market (Spring, 2015). At the

micro level, the introduction of neoliberalism in America’s schools creates a primarily economic

function, where students are not valued for their cognitive abilities but, rather, their ability to be

6

future workers, rewarded by the economic system (Tyack, 1976). Fine and Fox (2013) claimed

that neoliberalism diminished investments in the schools of low income communities, and, on a

more traumatic level, threatened schools by navigating public resources away from youth and

toward the criminalization of communities of color and poverty. The economization of education

impacts teaching practice, as now the aims of teachers should be to teach skills for students to be

future contributors to the workforce (Spring, 2015).

Changes in educational policy have not benefitted students and have caused harm.

Hursch and Martina (2016) argued that private actors like Bill Gates have greater influence over

education than the U.S. Secretary of Education. Through his funding, the Common Core

standards have been adopted in over 40 states, and he has influence over politicians, despite

possessing no formal background in education, nor expertise in global initiatives (Hursh, 2011).

Multi-national corporations like Pearson now develop most standardized tests in the U.S.,

thereby having influence over curriculum and student learning (Hursh & Martina, 2016). This

testing data is misused to promote corporate reformers and charter schools by putting

competition structures in place (Hursh & Martina, 2016).

“Consumers” use quality measures, established through testing, to select the best school

(Apple, 1993). Members of marginalized communities are disempowered by this process,

because they already to not possess a lot of “consumer” power. Apple (1993) warned that these

same quality measures for consumers, to select the best school, will create a system where

children are ranked. By legislators, policy makers, education systems, and families granting

legitimacy to market-oriented approaches, in education, it creates a situation where those who

deem what is appropriate in education actually mark and rank people, thereby turning the school

institution into a determinant of class (Apple, 1993). This leads to competition and national

7

testing that quantifies school outcomes, in order for families or consumers to choose schools

based on quality, and grants free market forces full operation (Apple, 1993). Inevitably, people

grant legitimacy to free market practices and this leads to an exacerbation of existing class and

race divisions.

This type of social segregation could depower students, and Apple (1993) identified this

as an act of hegemony. Testing data directly impacts students in another way, as it is in the

interest of reformers to prove increase in student learning by manipulating standardized test

passing rates (Hursh & Martina, 2016). Reformers utilize low testing scores among urban

students as justification for the establishment of more charter schools and school choice, and

they use this data to argue the ineffectiveness of teachers (Hursh & Martina, 2016). Students are

punished rather than rewarded by accountability reform, as these reforms undervalue diversity

(including learning, racial, and socioeconomic) (Graham & Jahnukainen, 2011). Reformers,

enmeshed in a culture of accountability reform, consider learner diversity a threat to standardized

performance indicators (Liasidou & Symeou, 2018). This is of great consequence for students

who do not conform to the standard, and they are viewed as not integrable into a neoliberal

society. Black and LatinX students are mostly pathologized as low-performers (Waitoller, 2020).

The education climate is negatively impacted by neoliberalism through competition,

exacerbated inequities, and the de-professionalization of education. The introduction of charter

schools further worsens inequities and bolsters neoliberal ideology. However, the most harmful

effect of neoliberalism is on student learning and teacher quality and retention. The most obvious

impact to student learning is the introduction of standardized tests, but in serving a competitive

structure these do not produce gains in student learning and data is manipulated to blame

teachers for ineffectiveness (Hursh & Martina, 2016). No longer are teachers crafting curriculum

8

tailored to meet the needs of individual students, but they must follow standardized curriculum

where learning is quantified. Through neoliberalism, an education system that values the

quantifying of student knowledge rather than providing care and developing a holistic learner has

been established. If a student is deemed unfit by test scores or cannot learn with a given

curriculum, they are pathologized and this impacts students of color the most (Golann et al.,

2019). Social inequities are merely reproduced through neoliberalism, rather than using

education to overcome them.

Through neoliberal reform, teacher quality is measured through quantitative data in the

form of test scores and evaluations in an effort to make teaching more professional. Gotz (1990)

warned against this and argued that professionalization of teaching is a cover for the

reproduction of capitalism. How teachers think and act has been transformed by neoliberal

education reform, due to increased accountability measures (Lipman, 2011b). In the U.S. teacher

quality is determined by performance on teacher certification exams, possession of advanced

degrees, and test scores (Boyd et al., 2005; Feng, 2014; Imazeki, 2005). Still, there is little

correlation between these measures of teacher quality and student learning outcomes (Betts et al.,

2003). Advocates for the neoliberal education reform movement believe that teacher quality will

improve through more regulations, and more stringent certification and licensing measures

(Angrist & Guryan, 2007). Despite more measures of quality, Berger and Toma (1994) found

that states with stricter teacher quality measures had students with lower SAT scores. However, I

adopt bell hooks’s conception of teacher quality. Quality educators know their students, know

their families, their economic status, their community, and how they are treated. They make

learning joyful and their classroom a place of pleasure. They also challenge students to think

9

outside their own values and beliefs. Quality teachers create a place where students can reinvent

themselves through knowledge (hooks, 1994).

Neoliberalism and Teacher Retention

No longer are schools a place of collaboration between teachers and students where they

make sense of the world, but are now places where teachers must focus on teaching to a test and

standardized curriculum (Hursh & Martina, 2016). A patriarchal tradition of authority relations

in education is replicated through reform quality measures (Apple, 1993). The school is

organized around a principal beholden to standards of the neoliberal state. With this structure,

teachers lose control over their own work (Apple, 1993). The trend in rationalizing curricula,

with created/prescribed curriculum, mostly impacts teachers. Apple (1993) addressed the state by

noting that the day-to-day interests of teachers contradict the interests of the state. Just because

the state wants to enact more efficient ways to organize and measure teaching, does not

necessarily mean that teachers will act upon these ways. The concept of intensification sheds

further light on this argument. The work privileges of educational workers and their sociability is

eroded through intensification (Apple, 1993). Intensification introduces new, technical skills that

a worker must adopt to keep up with the field, but results in less time to maintain one’s craft.

Intensification can reduce the quality of services (Apple, 1993). The use of pre-packaged

curriculum is growing in the U.S. (Sturges, 2015), and as a result teachers are just getting the

prescribed objectives completed rather than going above the norm and they do not have enough

time to be creative. Acceptance of intensification will generate different kinds of resistance, in

the form of quality of teaching (Apple, 1993).

Just because some neoliberal reform efforts look good on paper, it does not mean they are

effective (Sturges, 2015). Often neoliberal measures in education are manipulated to displace

10

blame for unemployment and the breakdown of values from the state or government to

ineffective teachers (Apple, 1993). If we examine neoliberal policy as a social practice, elements

of power emerge (Levinson et al., 2009), and these social processes serve as a way to change

what it means to be a teacher (Lipman, 2011b). Eventually educators who enter the field wanting

to provide quality education to students, embody neoliberal policy. Actors, who did not create

policy, participate and give consent to policy via actions that inform the societal norms of the

school (Spillane et al., 2002). Policy embodiment is iterative and impacts individual sense-

making.

Those that resist policy embodiment, leave the field of education. Currently, teachers

leave the profession at high rates nationally; 44% of teachers leave the field of education within

their first five years of teaching (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Not only does this have real

consequences for students, who are then exposed to a constant, new set of inexperienced

teachers, but the profession as a whole becomes largely de-professionalized (Darling-Hammond

et al., 2005). Bendixen et al. (2022) suggested that teacher perceptions of leadership, reform

policy, and safety in the school can impact teacher retention, both positively and negatively.

Charter Schools

The birth of charter schools is a significant example of neoliberal impacts on education

(Waitoller, 2020; Fabricant & Fine, 2012; Giroux, 2012). Although the future of charter schools

is vulnerable with politicians beginning to shift away from advocating for them (Berkshire,

2021), charter schools remain a topic in the education sphere, especially in Southern urban cities

rife with failing public school districts, gentrification, fiscal instability, reform, and racial

inequalities (Buras, 2015; Gabor, 2013). According to neoliberal ideology, before education can

be marketized, a range of alternatives must be established, and charter schools serve this purpose

11

(Lipman, 2011b). An added benefit for neoliberal and charter school advocates, individual

school choice is advantageous in that it shifts blame away from the institution or reform, to the

individual who has acted autonomously to select a school for their student (Hursh & Martina,

2016).

Reform-oriented individuals or organizations run charter schools, and these schools are

publicly funded but operated by private entities (Lipman, 2011b). These schools still function as

public schools and are beholden to follow federal laws to serve students with disabilities (Mac,

2022). In the 1980’s charter schools were seen as a means to create an education alternative in

poor communities of color, but this original conception was appropriated by philanthropic and

corporate entities (Fabricant & Fine, 2012). Explicitly, charter leaders established charter schools

to give voice to groups that have been marginalized or silenced (i.e. people of color or low

socioeconomic status) (Nathan, 1997), and advocates argue that the act of shopping for schools

empowers marginalized families (Mac, 2022). While charter schools introduce competition and

school choice into the educational marketplace, they also follow neoliberal ontologies of

competition and meritocracy with their enrollment of students with disabilities, while not being

able to provide adequate services and having high suspension rates (Mac, 2022), thereby creating

inequitable conditions for students. Charter schools play into tenets of neoliberalism by pushing

out unwanted students by withholding services and implementing severe disciplinary practices

(Collins, 2014). Therefore, the best rise to the top and this facilitates competition amongst

students. In short, competition is emphasized and not student learning or satisfaction (Waitoller,

2020).

Charter schools and school choice measures create competition structures that directly

impact urban families of color. These families often encounter poor public school choices in

12

their neighborhoods and are forced to seek out charter schools (Collins, 2014). The practices of

neoliberal school reform described, demand an education marketplace where schools act as

businesses competing for customers (i.e. students). Charter schools do so by promoting their

competitive advantage over public schools (Mac, 2022). Even with charter schools, this structure

forces students in under-resourced areas to compete for scarce resources, and this still leaves a

gap. A charter school might foresee a competitive advantage but the reality is they cannot afford

to actually provide service to all in the competitive education market (Mac, 2022).

School choice and charter schools also create re-segregation. Diamond and Gomez

(2004) examined how middle-class Black families and white families viewed school choice as

positive, as it promoted social inclusion, but working-class Black families developed a more

critical view of their neighborhood schools. Through competition, only a small portion of high-

performing public schools receive funding and this maintains the capital of white families in

gentrifying neighborhoods and schools (Lipman 2011a, 2011b).

Historically, charter schools have marketed themselves to families of color and justified

harsh disciplinary protocols, “no excuses” policies, and white-washed practices that may counter

a student’s home culture as a support to student academics (Golann et al., 2019; Johnson et al.,

2001). Because the charter school model is privatized, there is little room for community and

parent voice, and these schools, primarily serving students of color, hire white teachers or silence

the voices of teachers of color (Riley & Moore Mensah, 2022). Those few charters established

by Black individuals are more likely to close due to state-imposed standards (Kingsbury et al.,

2022). While scholars argue that opportunities in education must be redistributed, so those who

have previously been denied, have access, this does not occur in reality. Charter schools have

13

fewer access to resources and supports for students, and competition between schools results in

few to little gains in education quality (Waitoller & Kozleski, 2013).

Those who work in charter schools are impacted. Charter school teachers, particularly

women, exit high-poverty, high-minority schools not because of the students they teach but

because of a lack of support from the charter school, job dissatisfaction, better paying career

opportunities, and lack of control over decision making (Allensworth et al., 2009; Boyd et al.

2011; Buckley et al., 2004; Gulosino et al, 2019; Ingersoll, 2001; Kelsey, 2006). Teachers

remain in charter schools that provide administrative and collegial support, mentoring, and

professional development (Ingersoll, 2001; Kirby et al., 1999). Newly hired charter school

teachers are more likely to leave the teaching profession instead of transferring to another school

(Gulosino et al., 2019).

The Experience of Women in Teaching

Prior to the 1850’s, teaching in the U.S. was a vocation held primarily by men, but the

cultural and social changes prevalent in the nineteenth century brought women into the teaching

field and feminized teaching (Blount, 1999; Hoffman, 1981). By feminized, I mean an

overrepresentation of women in the field and the movement toward socially ascribed gender

norms (Blount, 1999). The industrial era ushered in labor shifts and the common school. With

this shift, men took jobs in more prestigious forms of economic productivity and women began

to take jobs in the common schools (Goldstein 2014; Griffin, 1997). As formal schooling gained

traction, the governess naturally transitioned to the role of teacher (Clifford, 2014). Although

these women were unprepared and unsupported for the discipline of urban schools and were

underpaid, the education industry welcomed women (Goldstein 2014; Griffin, 1997). A major

motivation for their admittance into the field was their willingness to accept less pay than men

14

(Tyack & Hansot, 1990), and the idea that women were the most desirable teachers because

formal education should be modeled upon the mother’s nurturing and instructive activities

(Clifford, 2014). Since then, the prominence of women as teachers remains, as 76% of public

school teachers in the U.S. are women (Walker, 2016).

Education in the nineteenth century focused on the delivery of rewards and punishment

and not the relationship between teacher and student (Clifford, 2014; Rousmaniere, 1994). At the

time reformers thought that to create a more humanized school, punishment needed to be more

gentle and not include physical force, in other words teachers were responsible for modifying

student behavior. Not only were women teachers responsible for this, but they were expected to

model self-discipline by following expectations from administration (Rousmaniere, 1994). These

teachers were expected to teach overcrowded classrooms, complete clerical work, manage

discipline and do so without complaint (Clifford, 2014; Rousmaniere, 1994). However, the

working conditions in urban schools in the 1920’s provided challenges for teachers to live up to

this expectation. Teachers experienced large class sizes, teaching in portables, and a lack of

resources. Students struggled transitioning from their communities into a classroom, and it was

challenging for teachers to impose middle-class values and teach academics, while students were

struggling to adjust to the culture shift (Rousmaniere, 1994). The chaos in schools at the time

was attributed to a teaching deficit, and not the class sizes, diversity of students, or working

conditions, despite this teachers were not provided with supports to address classroom

management (Rousmaniere, 1994).

In the current education climate, Pivovarova and Powers (2022) found that teacher

attrition is 54% higher in charter schools when compared to public schools. The gender make-up

of charter schools also mirrors that of public schools, according to the U.S. Department of

15

Education 2020 data 76.5% of charter school teachers are women (Will, 2020). Some scholars

argue that teacher attrition in charter schools is due to the charter school organization’s inability

to meet the needs of their teachers and lack of investment in human capital (Harris, 2007; Stuit &

Smith, 2012), and to lack of experience as many charter school teacher enter the field through

alternative licensure programs (Boyd et al., 2011; Fry, 2009).

In general, women teachers (charter or public) lament the lack of autonomy over their

lesson plans, and report having their lesson plans monitored by administrators. When they

deviate from these plans, they are reprimanded (Spencer, 1986). Women believe they have no

influence in school decisions, and report that they are not asked for input and do not feel

respected (Griffin, 1997; Noguera & Syeed, 2020; Valli & Buese, 2007).

Women teachers perceive that male administrators have too much control over their lives,

both at work and home. Work time is no longer confined to school spaces but is subjective, and

is a form of social time. Snyder (2016) defined social time as the rhythms humans create as they

interact in social institutions. Since work time now extends to projects outside the confines of the

space of the charter school, this poses constraints for teachers who now have work invade

multiple social spaces or fields, like the home. This explicitly impacts women teachers, who

report that the intense workload of charter schools causes them to leave because they feel like

they cannot start their own families (Olsen & Anderson, 2007). In this new labor market, work

time is conflated with social time as the lines become further blurred between work and home

life (Snyder, 2016), and the only way to meet the high-stakes expectations of urban public and

charter schools is sacrificing personal time (Griffin, 1997; Olsen & Anderson, 2007; Singer,

2020; Torres, 2014). Women teachers also report feeling isolated and perceive the establishment

of cliques based on administrator favoritism (Griffin, 1997), and bullying (Kezar, 2011).

16

In a study of four women teachers at a charter school in the Midwest, Singer (2020)

found these women met to discuss workplace hostility and issues of equity in hopes to challenge

the school’s policies. Ultimately, the opposition they faced from administrators caused them to

be disaffected from the school (Singer, 2020). These women were concerned about the high

work load, the hostile interactions with school leadership, and racial disparities in discipline at

the school (Singer, 2020). The women took their concerns to administration but were faced with

false promises and a non-inclusive culture. All four women chronicled that they worked late into

the night, had no work life balance, and felt judged when they did not conform to a culture of

workaholism (Singer, 2020). The school performatively advocated for self-care for teachers, but

one teacher felt shamed for taking time for herself and recalled a story of crying in the bath after

a full day of work. In another story, the women recalled how the school made the choice to

renovate a new building to maintain prestige, despite the women voicing that it seemed unwise

financially since the school was understaffed and under-resourced (Singer, 2020). The women

lamented that the school culture was reflective of that of the school’s CEO and principal—one of

white, middle and upper class ideals (Singer, 2020). This led to a culture of white, upper class

competition and messaged that a successful teacher would be a hyper competitive, white woman

(Singer, 2020).

Gender is directly tied to teacher attrition, with women 1.3 times more likely to leave

teaching than men (Borman & Dowling, 2008). While, many women teachers enter the urban

and charter school fields wishing to make teaching a lifelong career, they end up leaving the field

altogether due to policy, high work demands that detract from their personal life, burnout, and a

feeling of stagnation (Boe et al., 1997; Olsen & Anderson, 2007; Peske et al., 2001; Wenk &

Rosenfled, 1992). Society expects women teachers to meet high-stakes accountability demands

17

while maintaining a subordinate role within the teaching field (Lightfoot, 1978), and women

report that the intense workload of these schools cause them to leave because they feel like they

cannot start their own families (Olsen & Anderson, 2007).

Further complicating matters, many teachers enter the charter school field through

alternative licensure programs, and they are more likely to leave the field (Boyd et al., 2011). In

25 states, charter school teachers are not required to be certified and a large population of these

teachers have no teacher certification (Education Commission of the States, 2018).

Compounding this issue is Teach for America (TFA). TFA is a private-sector teacher

training/leadership organization that recruits, trains, and places its corps members (CMs) in low-

income urban and rural schools for two years (Teach for America, 2020). In 2018, TFA sent 40%

of its CMs to teach in charter schools (Waldman, 2019), and as of 2015 over 74% of CMs were

women (Del Ciello, 2016). This exacerbates the already high charter turnover rates, as TFA does

not envision teaching as a long-term career; rather, teaching is one stop on the path to a more

meaningful and/or lucrative career at higher levels of school administration/leadership, charter

school management, education policy, etc. (e.g., Anderson et al., 2022; Brewer et al., 2016;

Cersonsky, 2013; Jacobsen & Linkow, 2014; Trujillo et al., 2017).

Theoretical Framework

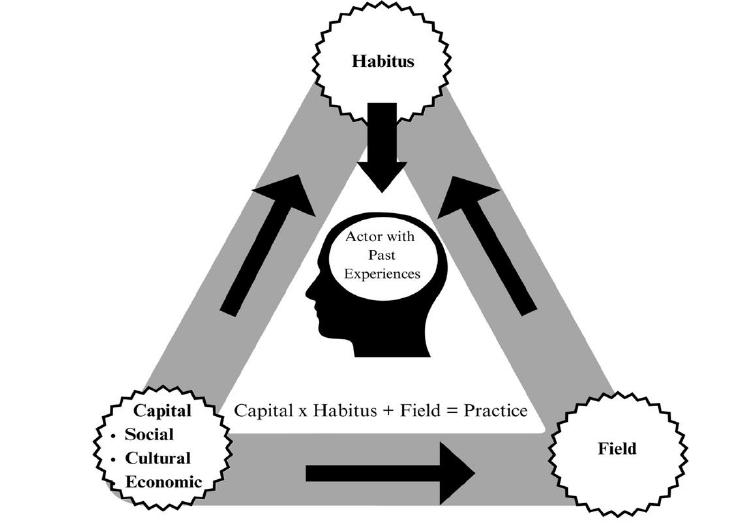

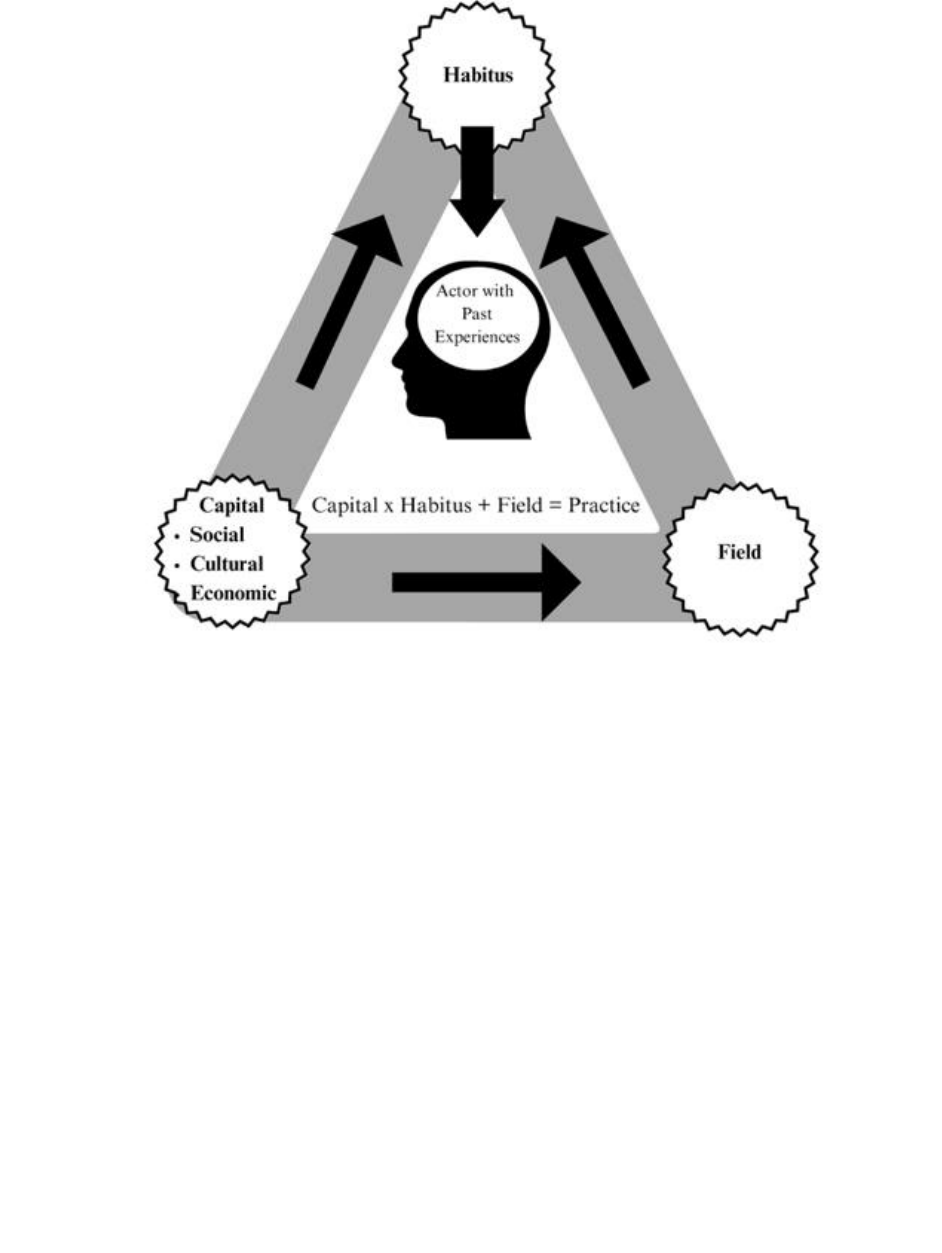

Analyzing Bourdieu’s Practice Theory (1977). Bourdieu

3

argued that culture is not the

product of free will or underlying principles, but social actors (humans with agency) construct

culture from dispositions structured by previous events. With this in mind, Bourdieu’s theory

3

Bourdieu was part of the poststructuralist movement. He began from a structuralist stance but his work moved

beyond this by challenging traditional notions of symbolic power (Robson & Sanders, 2009).

18

involves three major concepts-- habitus, field, and capital (Bourdieu, 1977). They converge in

practice.

Bourdieu conceived of capital as a toolkit, including cultural, social, and economic

capital (1977). For the aims of this work, I will not focus on economic capital because I am

interested in exploring the social and cultural rules that guide the ways of being for women

teachers within the field of the charter school, therefore I will only define social and cultural

capital. Of note, Bourdieu believed that all forms of capital incorporate economic capital, and

social and cultural capital are ultimately convertible to economic (Bourdieu, 1986). Social capital

references the quality and amount of resources within an individual’s network, and depending on

the characteristics of the network, social capital can give access to economic or cultural capital

(Bourdieu, 1984). Cultural capital is made up of social and cultural competencies, or knowledge,

of a particular field. It is bound to time and location, so context is important when applying

cultural and capital theories to an educational issue (Tichavakunda, 2019). In order to engage

with said context, Bourdieu turned to the concept of field.

The field is comprised of complex relationships that have specific forms of cultural and

social capital, and Bourdieu linked this to social worlds, with their own implicit rules. A field

can be any social world, including classrooms, charter schools, etc. One’s cultural and social

capital also depends on the field. Both Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) noted that capital does not

exist without relation to a field. Finally, the field links to habitus in that one’s behavior in the

field is shaped by the socialized norms reproduced in their habitus. I further explain the

interaction of these concepts in Figure 1.

19

Figure 1

Practice Theory Visualization

Note. Adapted from “Project-as-Practice: Applying Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice on Project

Managers,” by T. Kalogeropoulos et al., 2020, Project Management Journal, 51(6), 599-616.

20

The habitus is created through a social, rather than individual, process. This leads to

enduring patterns or habits, where society becomes deposited into agents to manifest lasting

dispositions or structured capacities that train social actors to believe and perform in determinant

ways that guide their actions (Wacquant, 2005). Of particular note to my research, the habitus is

created by the neoliberal structures of charter schools.

Within the structure of the habitus, individuals may not have identical experiences but

they share relational variants. The habitus can give birth to the integration of common

experiences, but personal and individual differences arise. Ultimately, for Bourdieu (1977), the

habitus served as a structure to unite these experiences into some position such as class. He

contended that the hallmark of practice is when something is performed through the body, in a

socially constructed space, to embody the structures of the world. As such, agents must abandon

notions of simple freedom or determinism. The practices of such habitus are self-regulated by the

agents, and these practices are developed to cope with unforeseen circumstances. Bourdieu

(1977) reasoned that agents are unconscious of these practices since the habitus is hidden under

its subjective nature. Habitus creates a commonsense world, and this theory provides the

framework to analyze how actors perform within the structures of habitus. This process is

bidirectional, as agents are not only influenced by the structure but influence the structure as well

(Bourdieu, 1977). Within the habitus, agents are constantly remaking their practices, conditions,

and the self (Skeggs, 2004).

Bourdieu (1977) challenged stagnant views of culture and institutional structure by

noting that culture constantly changes (Holland et al., 1998). While an institution, like the charter

school, might create behavioral expectations, these moments of constraint, caused by

expectations are not fully actualized until an entire interaction is complete. In simpler terms, no

21

matter how much ritual is involved, an agent still has control and agency in how they choose to

meet or resist expectations (Bourdieu, 1977). Covert forms of agency are introduced by

Bourdieu’s (1977) concepts of the rules of the game and playing the game. The “rules of the

game” are the cultural and social expectations created by the habitus, but agents might

consciously play by the rules in order to participate or survive in a system of power

(Smitherman, 2000). In doing so, playing the game becomes a performance of power and a

critical perpetuation of the process of inculcation (Bourdieu, 1977). At times, there might be

more to gain by obeying a rule or practice than resisting it, and it is in the best interest of the

agent to obey the rule. As long as playing the game is not the normalized practice, and the agent

is conscious of their agency, then they retain power (Bourdieu, 1977).

Under the new labor conditions created by neoliberal reform and charter schools, teachers

can have agency, power, and serve their own interests by engaging in serious games as they

pursue educational projects under these new conditions (Ortner, 2006). Ortner provided more

insight to the milieu involved in Practice Theory as subjects produce their world through practice

(Ortner, 2006). Following this theory, the structures of the habitus direct players how to perform

and act, however do not displace agency. Ortner (2006) focused on the agentive action that

remakes social structure, and brings into focus more complex forms of social relations like

power and subjectivity. To Ortner, the agent is always enmeshed within relations of power and

inequality, which she felt was ignored by Bourdieu (1977).

In serious games, social life is seen as something that is always played, according to

cultural goals, and focuses on complex forms of social relations like relations of power (Ortner,

2006). Ortner (2006) problematized agentive action and recognized its limits. She argued that

agents are always involved in social relations and can never act outside the relations with which

22

they are enmeshed. With this idea, all agents or social actors have the potential for agency, but,

while they are engaged with others in the act of serious games, it is impossible to imagine them

as completely free (Ortner, 2006). In serious games, power trumps acts of social solidarity

(Ortner, 2006). While agency is universal, it is also culturally and historically constructed, so at

different points in time it could look different.

Further complicating the education world, much like neoliberalism, the concept of

flexible capitalism refers to the economic transformations that hit the U.S. between the 1970’s

and 1990’s. Flexible capitalism introduced new forms of production, exchange, and human

resources to change the structure of the workplace (Snyder, 2016). A tenet of flexible capitalism

is that it focuses on uprooting the traditional chain of production, much like how the introduction

of charter schools uprooted traditional systems of education with the introduction of competition

and educational marketplace. This phenomenon is the work of the elites and policymakers in

order to innovate and promote the abstract over the concrete (Snyder, 2016). New ways of

production that can adapt and re-tool to an ever dynamic economy are promoted, with the intent

to push out the old way of doing things (Boltanksi & Chiapello, 2005; Cappelli, 1995).

I can tie flexible capitalism’s concept of core employees to Bourdieu’s concepts of social

and cultural capital as well as habitus. Employers invest a lot of capital into their core

employees—permitting them perceived decision-making power. However, core employees are

presented with this illusion of autonomy so they will align with the company’s mission and work

towards it. This creates a habitus where overworking is the norm and a sign of dedication. In the

charter school, the same culture is created where the expectation is workaholism and teachers

feel judged when they do not conform to this standard (Singer, 2020). Adding to this burden, the

flexibility of actual work stuff has changed. In a world where a work project can be completed

23

virtually or on a computer screen, this means workers can take work with them wherever they go

and that becomes the expectation (Snyder, 2016). Work time is no longer confined to space but is

subjective, and is a form of social time. Snyder (2016) defined social time as the rhythms

humans create as they interact in social institutions. This could be compared to the habitus or

ways of being that are created within the space of a charter school. However, since work time

now extends to projects outside the confines of the space of the charter school, teachers are

constrained as they now have work invade multiple social spaces or fields.

While other scholars have taken up Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice, there is a gap in the

literature surrounding Practice Theory and techniques teachers develop to remain in the field and

the educational process, and, undoubtedly, a hole when it comes to the charter school setting. In

educational research, the majority of literature centers around Bourdieu’s theory of cultural

reproduction and the role of habitus in socially constructed realities. Practice Theory can help

teachers become aware of how the field and habitus create social norms, and that they have

agentive action to change and disrupt these norms from within. Other education scholars have

dismissed Bourdieu’s theory of cultural reproduction, found the concept of habitus incoherent,

and have argued that it is unhelpful in educational research (Beckman et al., 2018; Sullivan,

2002). Sullivan (2002) contended that the concept of habitus is incoherent and too nebulous and

ambiguous. What this ignores is the possibility for habitus to be a valuable tool for teachers in

making institutional changes from within, and the agency that they possess to do so. Like

Sullivan, Beckman, et al. (2018) viewed Practice Theory as a challenge for educational

researchers, as its methodology is difficult to comprehend. These authors saw value in using

Practice Theory as a new approach to investigating technology practice across students’ lives.

However, this research only incorporated Practice Theory as it relates to students. It has been

24

proposed that a discourse between Practice Theory and Critical Race Theory

4

(CRT) is needed to

study inequities in education, as CRT has never fully engaged with Practice Theory

(Tichavakunda, 2019). Tichavakunda (2019) found value in Practice Theory’s use in educational

research in that it can inform CRT, and open up possibilities for discourse between other theories

and CRT to better understand racialized realities of education.

Just as Practice Theory is valuable to understand the realities of students, it is also for

teachers. As noted, Bourdieu contended that the hallmark of practice is when something is

performed through the body, and my research will illustrate how teaching and institutional

practices become embodied practice. More time is spent in practice than actually in the social

world, and I propose that my research might illustrate the burden of spending more time with the

field of institutional politics rather than in the field of the classroom.

Through Practice Theory, how individual sense-making is developed is deconstructed,

and this can be utilized as counternarrative. Broadly, this application introduces a new approach

to considering educational policies through the bodies and fields of women teachers. Snyder

(2016) argued that good work and a good life might be difficult to reckon in an era of flexible

capitalism. With this in mind, I argue that resisting the charter school field might not result in

overt acts of violent opposition, still may contribute to institutional projects, but agentive

resistance can be minimal and transformative if teachers analyze all projects for which they are a

part (Ortner, 2006). Teachers may be creative with their resistance by having a trusted mentor,

choosing to independently alter their curriculum, or simply stopping work at the end of their paid

4

Critical Race Theory in education places both race and racism in historical and modern contexts through

interdisciplinary methods. This theory challenges the discourse on race in education by analyzing how education

theory, policy, and practice have been used to marginalize certain ethnic and racial groups (Teranishi, 2010).

25

work hours. These covert ways disrupt oppressive power structures and creating possibilities for

new structures.

My research will represent an important counternarrative to the literature, which

characteristically focuses on policy, culture, or students; not the individuals who teach in

schools. For women, academic work is emotional labor (Cummins & Huber, 2022; Selberg,

2020). Furthermore, our understanding of the realities of surviving in a charter school, controlled

by neoliberal policies that impact teacher experience and practice, is expanded. Scholars have

suggested that charter schools fail to take advantage of their autonomy when it comes to practice,

and there is a trend toward standardization of practice rather than innovation in charter schools

(Hubbard & Kulkami, 2009). This indicates that Practice Theory is well-suited to analyze

outlying incidents of autonomy in the field. Analyzing Practice Theory has the potential to offer

insights into how women charter school teachers could uphold legitimacy and resilience in the

field. It can also spotlight how teachers comprehend their roles within the charter school domain,

potentially fostering retention, as well as reconfiguring and challenging the embodiment of

policies and the structures of educational work.

While few scholars take up Practice Theory (1977) with arts-based (ABR), narrative, or

autoethnographic methods, there is a natural connection to Bourdieu and arts-based

methodologies. Some researchers in the arts utilize Practice Theory to explain how practice is

embodied (e.g. Banks, 2012; Rimmer, 2017), and I argue that methods like autoethnography,

narrative, and ABR viscerally capture the experiences and practice of actors (Bochner & Ellis,

2016). Some researchers have used Practice Theory in conjunction with ethnographic methods

(e.g. Ghaffari et al., 2019; Thomas & Epp, 2019; Svensson, 2007), and these studies noted that

26

ethnography is a method well-suited to work with Practice Theory to capture the culture and

social ways of being in a particular field (Hackley, 2019).

ABR used in tandem with Practice Theory relies on the embodied exploration of social

practices, and performance methods embody and bring to life the practice that is the

phenomenon of research (Barone & Eisner, 2012; Leavy, 2015). Narrative and autoethnographic

methods also reveal cultural meaning and values and how these are negotiated in the field of

study. Ultimately, these methods, when paired with Practice Theory, can offer a creative way to

examine the complexities of social life and how practices are shaped by culture and power (Hui,

2015).

Research Questions

The purpose of my dissertation is to explore the habits and enduring patterns created by

neoliberal structures that dictate how women teachers should behave within the culture of a

charter school and uncover how my participants resist and describe their own resiliency within

the charter school institution. Specifically, my work is grounded in the assumption that teacher

success in the labor force is inhibited by institutional rules that are ultimately harmful, and cause

teachers to leave the field of teaching (Boe et al., 1997; Olsen & Anderson, 2007; Peske et al.,

2001; Standeven, 2022; Wenk & Rosenfled, 1992). To critique the culture of charter schools, and

to interrogate systemic inequities I will explain how Practice Theory can add insight to the

education process, and how agents have the possibility to change their habitus and resist

(Bourdieu, 1977). I want to uncover what hidden rules are deposited into teachers and how

teachers might resist these rules and alter their habitus. The research questions that will guide

this dissertation include the following:

27

1. How can documentary narrative analysis be used to allow a researcher, with

insider knowledge, to give voice to the stories of participants, in order to examine

the neoliberal structures, inherent in charter schools, that create a habitus?

2. How did I use agentive action, as a woman teacher, to remake the social structure

of the charter school institution?

3. Do women teachers resist the hidden rules of the charter school institution? If so,

how?

4. How do women who work as charter school teachers describe the techniques they

have developed to in order to remain working as teachers?

This application will add nuance to the current research landscape, but on a broader level it

introduces a new approach to considering educational policies through the bodies and fields of

women teachers. This approach has the potential to provide insights into how women charter

school teachers might maintain resilience in the field, and highlight the ways in which teachers

who have become disillusioned with the field can make sense of their role within the charter

school field which could lead to retention in the field, and recreation and disruption of ways of

policy embodiment.

Philosophical Commitments

My epistemological and ontological beliefs are influenced by the concept that power

pervades every level of social relationships (Barker & Jane, 2016). My work utilizes both critical

and post-structuralist paradigmatic orientations (Harris, 2001). I adopt these orientations because

many critical post-structuralists acknowledge that policy does impact gender and racial groups

(e.g., Bohrer, 2019; Foley, 2019; Harris, 2001), and recognize neoliberalism as manifestation of

power (Apple, 2012; Kincheloe & Mclaren, 2002). Particularly, critical researchers view

28

research as a vehicle for empowerment and social change (Kincheloe & Mclaren, 2011), and

Kincheloe and Mclaren (2011) pose a call to action that researchers must resist neoliberalism. I

do seek to empower women charter school teachers, but I know that I will not be bias free

because this work is inspired by my own teaching experiences.

I take the ontological stance that there is no objective truth and any supposed truth

contains contradictions (Sipe & Constable, 1996). Epistemologically, I believe that reality is

subjective and constructed on the basis of issues of power, and it is, ultimately, unknowable. I do

not abandon critique, and ultimately know that discourse, particularly my discourse, is

inseparable from myself as a researcher. My discourse is vulnerable and contingent upon time

and place. Adopting this orientation is most appropriate for this research as I seek to construct

meaning through reflexivity toward my experiences and those of my participants, and I wish to

make meaning from these experiences to decipher how participants viewed occurrences

(Richardson & Adams St. Pierre, 2005). I also accept that conversations with participants are

incomplete and partial (Jackson & Mazzei, 2011).

Language is systematized by structuralism, but my focus is not on the structure but upon

what is left over, which can birth to readers garnering their own interpretations from participant

stories (Lather, 1992). As my methodology involves interviewing, my belief that the charter

school institution is harmful will be ever-present. Having, myself, been oppressed by power in

the charter system, it is impossible to mask my values as a researcher, and they are always

present in my work. I am not neutral. As a former woman charter school teacher, I attempted to

recreate my social world and resist the culture of the charter school institution, both consciously

and unconsciously. I also left the charter school field because I felt it harmed my development as

an educator, so this certainly is a bias I possess. I accept that my experiences and feelings toward

29

the charter school institution will influence my research. Personally, I feel some guilt leaving the

charter school teaching field, because of the students I left behind. I entered the field thinking

this would be my lifetime craft, and when I faced challenges I left. Maybe to alleviate my own

guilt, I pursue this work to change conditions so that women teachers do not have to feel

beholden by institutional structures, can perform their craft, and will remain in the field.

In my research, my aim is not to diagnose or prescribe a problem because I do not believe

in an absolute truth or solution. Rather, I will provide a conduit to share the experiences of those

who have worked in the charter school culture. My hope is to share stories that others might find

connection to or help them reflexively explore their own realities within the charter school

institution.

My critical leanings recognize that the values of the researcher are present, I know this

will influence the research. Most importantly, this paradigm examines systems of power and I

will explore the realities of these teachers within the cultural context of the charter school. Like

Vennes (2022), Brunner (2003), and Buras (2011), I strongly believe that charter school

institutions are patriarchal in nature and their very existence and rhetoric, used within these

spaces, is rooted in power and domination.

Manuscript Overviews

I will complete a three manuscript dissertation (see Appendix A for individual manuscript

details), and what follows outlines my methodological considerations for each manuscript.

Details of each manuscript are followed by my positionality. Collectively, I use general

qualitative research methods because I am seeking to explore a topic of inquiry through

conducting social research (Saldaña, 2011), and I believe in multiple truths (Sipe & Constable,

1996). I use interviewing and journaling as the data collection methods across all manuscripts,

30

both because of their appropriateness and they are the data collection methods with which I have

the most experience. Interviewing is well-suited to answer my research questions, as I want to

understand how the participants themselves describe their resiliency and experiences. In the past

I have conducted over 22 interviews with marginalized populations, and have been able to reflect

on my practice and learn from previous interviews to improve my interview style. I value

listening and connection with participants (Roulston, 2010), and interviewing captures a true

picture of the experiences of my participants and the culture of the charter school setting.

Manuscript 1

The purpose of this study is to explore a methodological and analysis technique that

allows a researcher, with insider knowledge of their participants, to share their stories to

empower (Kincheloe & Mclaren, 2011). I ground this work in the theoretical frameworks of

Bourdieu’s Practice Theory (1977) and Ortner’s (2006) serious games. In my own research

experience, I have been forced to follow traditional ways of research where I must follow a

specific format, impose my interpretations upon data to conduct an analysis, and have been told

that narrative or “newer” methodologies (e.g. autoethnography, poetry, or ethnodrama) are not

rigorous. Because I believe that there are no objective truths, I do not deem that researchers need

to provide a discussion of an analysis (Cook & Bublitz, 2023). I present the usefulness of using a

documentary narrative analysis, formed from narrative methods, in order to attempt to inspire

change and empower my participants. Furthermore, this approach expands understanding of the

realities of surviving in a charter school, controlled by neoliberal policies and tenets of

capitalism that impact teacher experience and practice (Boe et al., 1997; Olsen & Anderson,

2007; Peske et al., 2001; Wenk & Rosenfled, 1992). The research question that guides this study

is as follows: How can documentary narrative analysis be used to allow a researcher, with insider

31

knowledge, to give voice to the stories of participants, in order to examine the neoliberal

structures, inherent in charter schools, that create a habitus?

I begin with a review of literature that highlights neoliberal reform efforts that alter

educational work (Olsen & Anderson, 2007), the structure of charter schools, and flexible

capitalism and its impact on core employees and work time (Snyder, 2016). Next, a presentation

of the theoretical framework of Practice Theory and serious games provide the lens and

foundation by which to understand the habitus and enduring patterns created by school

institutions that dictate how women teachers should behave within the culture of a charter

school. I follow this with a description of my documentary narrative methodology and analysis,

and conclude that this is a valuable tool when conducting research with participants with whom I

share knowledge. I conclude with my findings and a discussion rooted in how researchers may

use this methodology to subvert the tradition set forth by the academy and to consider how

educational policies manifest in the bodies and fields of women teachers.

Methodology

I used narrative methodologies and my own background in documentary film to build a

framework I label documentary narrative (Cook & Bublitz, 2023). I did so to help explore how

my participants might describe the impact of neoliberal structures on their work habitus.

I interviewed two women charter school teachers from the Southeast United States. I

label my sampling as critical opportunistic (Miles et al., 2020). I taught in the school site and

worked with the teachers that were interviewed. I had easy access to these teachers and my prior

knowledge of their experiences fits well with my purpose. Both participants have taught English

language arts for at least three years in the charter school setting. My participants both worked in

a 6-12 Title I charter school. I interviewed each participant twice using an interview guide where

32

I asked them about the rules that govern their practice, how they remained resilient in the

teaching field, and how they were supported by administrators. In addition to interviewing, I

engaged in deep hanging out, when the researcher spends time with participants in informal

settings to lessen the role of being an outsider (Geertz, 1998; Woodward, 2008). To do so, I

immersed myself in my participants’ culture, observed participants in informal settings outside

of the charter school, attended after-school happy hours, and engaged in short phone and text

message exchanges. I recognize the limitations of the selection in that my familiarity with the

site and participants brings with it multiple assumptions and a priori knowledge to the work. My